El Morro

The Castillo San Felipe del Morro, once the most formidable fortification in the Caribbean and its companion Fortín de San Gerónimo del Boquerón that protect the city of San Juan, Puerto Rico, were never taken by force of arms.

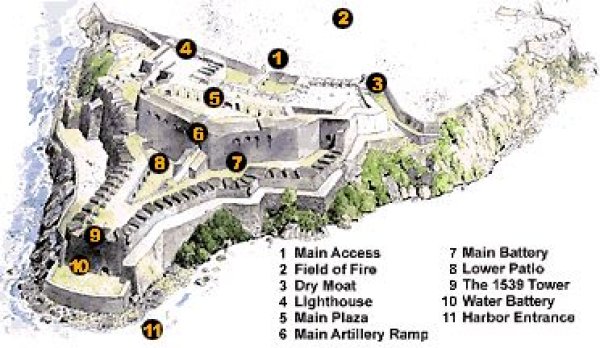

El Morro is a Spanish term meaning "The Promontory" and it is aptly named as it sits on the peninsula that juts out to form the bay and harbor of San Juan. Construction began in 1539 under orders of King Charles V of Spain. In 1587 engineers Juan de Tejada and Juan Bautita Antoneei designed the fortification that stands today. It was based on the principles used in many other forts throughout the Caribbean. Additional structures were added over the next 400 years, to keep up with military technology. Walls that were originally 6’ were by the 18th century, 18’ thick. Ultimately El Morro has six levels that rise 145' above the sea. All along the walls are sentry boxes known as ‘garitas’ which have become a cultural symbol of Puerto Rico.

Throughout the history of Spain’s ‘conquest’ of the Americas, El Morro stood to protect the valuable routes from Mexico, Peru, the Philippines (via Panama) and Columbia. It was the last stop of the treasure fleets before crossing the Atlantic. As such it made for a tempting target for those nations who envied the Spanish hegemony and the riches it brought to Europe and for hundreds of years made the Spanish Empire the most powerful on earth. So naturally there were many attempts to take it.

Sir Francis Drake, the English privateer and his cousin Sir John Hawkins tried on November 22, 1595 with 27 ships and 2,500 men. During the attack Hawkins died on board, off the Puerto Rican coast. Drake abandoned hope and set sail.

Drake developed dysentery during the battle and died off the coast of Panama in January of that same year.

A Dutch fleet tried on September 24, 1625. Although they did burn the city of San Juan, they failed to take El Morro. In fact they found themselves trapped in the harbor that they had so boldly penetrated and then had to run the gauntlet of El Morro's guns to escape.

They left behind a great prize, the 30 gun 450ton Medemblik.

Final casualties: Spanish/Puerto Rican = 17, Dutch = 200

One of the largest British attacks on Spanish territories in the western hemisphere consisted of 13,000 men and an armada of 64 ships commanded by Sir Ralph Abercromby. Although both sides suffered heavy losses, the British suffered one of the worst defeats of the English navy for years to come. The British ceased their attack and began their retreat from San Juan on April 30, 1797.

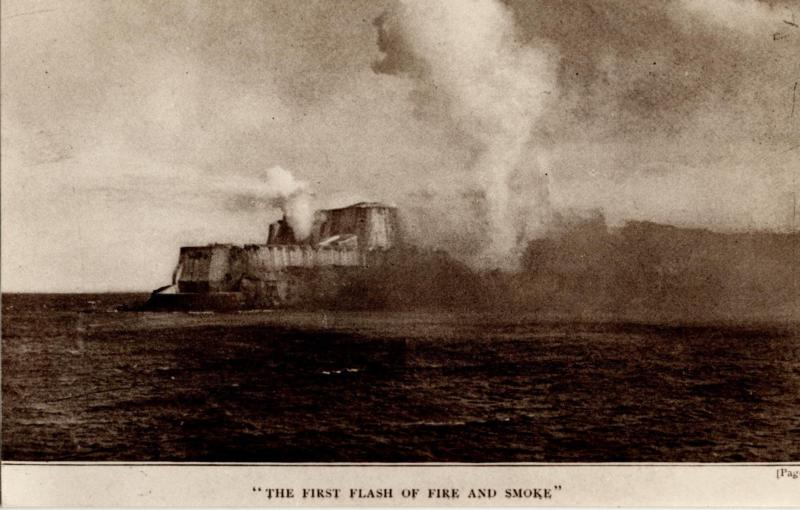

In 1898 during the Spanish American war, the Yanqui fleet under command of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson which included the dreadnaughts USS Iowa and Indiana, 2 monitors, torpedo boats and cruisers, bombarded El Morro three times and blockaded the port of San Juan.

El Morro was severely damaged and so the American battleships turned their attention to San Cristobal, the infantry barracks and some lesser coastal defenses. Casualties were extremely light on both sides. The American fleet sailed off to blockade Havana, Cuba.

The island was later invaded from the opposite side at the town of Guánica in the South, in order to avoid having to storm El Morros' defenses.

When the Spanish surrendered to the Americans and the war ended, the forts were still undefeated.

The first shots fired by the U.S. in World War I, came from El Morro when she trained her guns on an armed German supply ship trying to resupply U-Boats waiting off shore.

During World War II the United States Army added a massive concrete bunker to the top of El Morro to serve as a Harbor Defense Fire Control Station tasked with directing the network of coastal artillery sites, and to keeping watch for German submarines which were ravaging shipping in the Caribbean.

The United States Army officially retired from El Morro in 1961. The fort became a part of the National Park Service, to be preserved as a museum.

The Castillo and the city walls including San Gerónimo, were declared a World Heritage Site by the United Nations In 1983.

The symbol of Puerto Rico stands to this day and is a badge of honor, un-defeated and proud, welcoming tourists to share in its history.

¡Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre!

TWO FOUNDERS FLOUNDER IN MILENNIAL MIASMA

This is a colloquy between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, about the U.S. Constitution of 1787/89, The Bill of Rights and the 2nd Amendment in particular.

JEFFERSON: As you will recall, James, I was in Paris when I received the draft of yours and the others’ brilliant work In Philadelphia. I was astounded as to its completeness with regard to the mechanics of government.

MADISON: Yes, I very vividly recall that letter. You were quite busy with matters of state. Generally, you did concur with the body of work as presented; however, you minced no words as to your disappointment at the absence of a bill of rights.

JEFFERSON: I was incensed. There was no protection for religious freedom, or that of the press, or against standing armies -- Hah! What a turnaround; in the 21st century, it is the standing army, navy and air force of the United States which protects that portion of the world that has adopted the ideals we brought to the fore!

MADISON: So it is. In that regard, another inclusion in the final Bill of Rights, pertaining to firearms, has been grossly misinterpreted – rather, grossly compromised – to a point where the domestic peace of the nation is being destabilized.

JEFFERSON: We merely assured that citizens not be deprived of having a musket at home, in order to be at the ready at a moment’s notice, in defense of the new Republic.

MADISON: That which turned out to be the 2nd Amendment should have been abolished by the time the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments were adopted. Those quaint ideas, by that time, were more than demonstrably proven to be moot.

JEFFERSON: Nevertheless, in the middle of the 20th century, manufacturing greed and the desire to wield political control caused an otherwise inoffensive shooting club to sanctify and misuse that pitifully out of date 2nd Amendment.

MADISON: Eighteen years into the 21st century, the almost unrestricted availability of weapons we would have seen to have been delivered directly from the bowels of hell are finding themselves in the hands of individuals who are most deeply disturbed. In turn, unsuspecting adults and children going about their daily lives suddenly are maimed and murdered on the spot!

JEFFERSON: The pity is, we are held to blame! There has grown up a holy army that hails itself the defender of the 2nd Amendment. They imprint upon us the intention to provide each and every citizen with whatever of those fiendishly conceived weapons he… (OK, …or, “she”) desires. Nothing could be further from the truth.

MADISON: No, no, no… People of the 21st Century, use your good sense. We were primitives, protecting ourselves in the only way available to us. That protection for you is afforded by the same forces that protect the current free world. The Constitution allows for changes that come with changing times.

JEFFERSON: Would that we could get that message through to them – along with another matter I expressed in my December 1787 letter to you – (to use a modern expression) an idea I seemed to have knocked out of the park!

MADISON: What on earth would that be, Thomas?

JEFFERSON: Regarding the three branches, while concurring with reasoning’s for the restraints placed upon the Executive, in addition, I expressly suggested that someday a foreign leader might be tempted to insinuate himself directly into our election process.

MADISON: Point well taken, Thomas!

A Private Confederate Monument

A black and white Polaroid taken by my grandfather commemorates one of several pilgrimages we took by bus back to his birthplace in north-central Georgia. The scattered village where he was born is a remnant of what was once the family plantation. The sound of U.S 441 rumbles nearby.

This was over fifty years ago, and memory is an imperfect monochrome. I was an annoying child eager to ham for the noisy, black-bellowed Model 95 Land Camera, a contraption as sophisticated to me as a Gemini orbiter, and as ever present as his pipe and fedora.

“Now, then…,” he would repeat, applying the gum stick to several prints, ostensibly to prevent their fading too quickly. The chemical stench of the gum was as familiar as the aroma of his preferred Prince Albert tobacco.

He was quite elderly when I was small and I was his only grandchild, something he would remind me of when I became a morose teenager. He also reminded me that he had never known his own grandfather because his had died in the Civil War. What is distant history to most has always been to me something closer in proximity.

Perhaps my obsession with history originated from the infrequent talk of this martyred Confederate Corporal, a reluctant ghost. A copy of a pre-war Ambrotype, which hung for years in grandfather’s living room, shows a confident, handsome fellow. Died at the Battle of the Wilderness, was erroneously repeated.

My Grandfather had the unusual middle name Napoleon. He said he had no idea how it came to be. I discovered years later that his grandmother, the Corporal’s widow, had a brother with the same name. Something inexplicably never discussed, like the absent Corporal, the central tragedy of their lives.

One vivid recollection has had a lasting impact: At a country store, an unpainted shack bedecked with coca-cola signage and festooned with yellow fly strips, grandfather and I encountered one of his childhood companions. When introduced—I had yet to meet a black person in my life—the old fellow leaned into me and demanded to know my last name. When I told him, he exclaimed, “Well that’s my last name too! Do you think we might be related?” The adults present had a good chuckle, but it would be some time before I understood the darkness of their humor.

The Patriarch, the Corporal’s own grandfather, had been an adolescent militiaman in the Revolution. He lived nine decades and accumulated twenty square miles of cotton fields and piney woods. As a state assemblyman and senator, he played a role in dispossessing the Cherokee of the Dahlonega gold fields, and his eldest lawyer son acquired and managed a mine for the benefit of the whole clan. The plantation property was mostly tenanted. The number of slaves in the record is fewer than one might expect.

A family history typically portrayed the old man as a benevolent master, his tolerance of the peculiar institution both sanctioned and forgiven by pious Calvinism. His will allowed his slaves to live with any of his children or grandchildren they preferred. Two sisters were to remain together permanently. The men permitted to visit their wives once a week. These instructions were enforceable by punishment of “forfeiture” he proclaimed, to what entity other than manumission he failed to disclose.

The Corporal and his brothers, all of whom survived the war, were by no means raised as pampered aristocrats, all having learned separate trades. His was with the hammer and anvil. He married late, courting the daughter of a tailor in Augusta. His only child was an infant when he abandoned them for the army. The wife never remarried, receiving a widow’s pension well into the 20th Century.

If abandonment is too strong a term, being a member of the militia was required by law. This was true prior to the Revolution as it is required unofficially even today. Its primary mission then was to organize slave patrols. The militias also mustered regularly for social events, summer picnics and political speeches, parading for the admiration of eligible ladies in garish homespun uniforms. When the drums of war became deafening the militias eagerly morphed into combat companies, and those same admiring ladies encouraged them onward with appalling enthusiasm.

For a time I lived vicariously in the combat prowess of his regiment, the 18th Georgia Infantry, famously brigaded with three from Texas under General Hood. That first winter at Dumfries, Virginia, they died in large numbers of childhood diseases, mumps and measles. The brigade then fought gallantly at Gaines’s Mills, and then at Second Manassas, where they spearheaded Longstreet’s assault on Pope’s left, scattering the Yankees in retreat. They captured two stands of colors and a battery of cannon, decimating the 5th New York Zouaves so completely its survivors served out the remainder of the war as reservists and hospital orderlies.

I have since doubted his direct involvement in combat. He was forty years old, officially designated in the muster rolls as regimental blacksmith. I imagine him instead bringing up the rear, a wagon driver hauling supplies and smithy tools. The injury that killed him—dropping a hot horseshoe into his boot, in an army nearly bereft of shoes—confirms for me this conjecture. The accident happened at camp after the retreat from Antietam. He lingered for several days at a hospital in Richmond and died of tetanus.

As the conflict drew down, the Corporal’s widowed aunt, rumored to have squandered a small fortune in useless Confederate bonds, resisted reconstruction even in death. Early in 1865, with the neighborhood occupied by Yankees, she solemnly made out her last will and testament, disposing of all property she still possessed, including a handful of slaves she technically no longer owned. A finer point to her grief and oblivious fanaticism, she willed a “Negro boy named Jefferson” to her nephew the Corporal, already known to have been dead three years.

Grandfather liked to repeat the story how his orphaned father, at the age of six, was detained for throwing rocks at the Yankees as they marched through the village. The intervention of his black “Mammy” rescued him from the angry officers.

My interest in family history and the Civil War has waned over time as new interests preoccupied. I once stumbled upon a reenactment camp, fascinated by the costumes and the detail of their accoutrements. A friendly re-enactor invited me to join the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization dedicated to honoring and preserving the heritage of this defeated army. The conversation devolved into the same Lost Cause apologia and equivocations I had already adequately studied; The South had a right to secede. The war was not about slavery. The business card he proffered I tossed into a desk drawer and forgot.

Devotion to tradition and heritage is noteworthy, but slavery is vile and treason dishonorable. It doesn’t seem we will ever arrive at a neutral place where the symbols of this struggle can quietly coexist with the lingering, abhorrent reality of it. The fate of battle flags and statues will become what they need to become someday: fading and tumbling into irrelevancy and rubble.

The Corporal’s monument in Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond, unlike the mass-produced effigies of the men who lead him and his comrades to slaughter, is a square numbered block shared with two other men. I had once acquired, but long since misplaced, the number of his unvisited grave. This has always been the ultimate Confederate monument, and for me a personal and private memorial.

Fifty years ago, Grandfather and I struggled up into the woods behind the old place. He showed me a grand old tree with a knot half way up the trunk, a knot he had tied into it as a boy when it was still a sapling. It was an awesome curiosity. If there existed an old Polaroid print of it, it would be a dull thing by now. But somehow I know even without it, that there is no possible way that that tree still stands.

Terrible Knowledge

A text for performance

In memoriam Walter Benjamin

"Human beings live emotionally on the surface with their surface appearance. In order to get to the core where the natural, the normal, the healthy is, you have to get through to the middle layer. And in that middle layer there is terror. There is severe terror. All that Freud tried to subsume under the death instinct is in that middle layer. He thought it was biological. It wasn't. It is an artifact of culture. It is a structural malignancy of the human animal. Therefore before you can get through to what Freud called Eros, you have to go through hell." - WILHELM REICH INTERVIEW 1952

For Nicholas Lathouris & Anna Zabawski

NOTE for performance:

Terrible Knowledge was originally written as a companion text to Ulrike Meinhof Sings (1983). I had in mind a duologue. Its first incarnation was as a filmtext in 1987. I have worked on it intermittently for five years, 'reading' the text in a performance environment. I wanted to have this gestation period for the work for moral as well as technical reasons. As with Ulrike Meinhof Sings I know I am going beyond the conventional norm for a monologue in every sense & it is crucial for me to test my transgression under the gaze of rigorous colleagues & audience. Clearly I am not dealing with 'character' but presence and given the material of this text I wanted as accurate a blueprint for performance as I could possibly construct. Each & every text has a time to utter & it has been clear to me for some time that I had reached this point with this particular text.

The final draft of this text was completed in Paris, France 1992

Excerpt 1

****

HEIMANN: There's rats in hell. There can be no doubt about that. Some of them were up in the air. All the time. They were confused. Yes. Certainly. Others served themselves. I remember his name. Chaim Bukowski. In the Great War. We made use of our Chaim Bukowski. We made him king over his people. That made him happy. He was master over his tribe. The chosen ones. Bukowski grabbed quickly the power we gave him. Power made him happy in his environment. Make no mistake. He was more sordid than I. I gave him power to be judge and executioner. He was the judge of high and low. He raised taxes. Coined money. This Bukowski surrounded himself with courtiers and flatterers. He had singers and poets dedicate their work to him. He commissioned homages to himself. What kind of man was this. He was a slave. Like the others. He was our slave. That's the simple truth. This man could not or did not want to understand his condition. On anything other than day to day business he had already closed his old eyes. He was good enough to command others but he was also chief amongst those we gave a good beating. Bukowski displayed all the pomp and ceremony of a head of state under his ridiculous beard. He struck off postage stamps with his own face imprinted on them. Our Bukowski appeared in public in a white coat and cap that he kept for his personal use. He had the power to arrest and pardon his subjects. This man interested me — not because he was rare — there were many Bukowski's — it was because he rushed to serve us quicker than we went to him.

I talked to this old fool over some ersatz coffee one night in what he would call his palace which was in actuality a small hovel in the ghetto. It was once the hall of a Roman Catholic Church I believe. He said his aim was to achieve peace in hell. He would say — my children, my slaves — I have a mission — to save the slaves in hell. This Bukowski had taken on the airs of an old prophet. He thought he was going to take them through every peril. He truly though this. When he was deported with the last of them — he was shoved into the cattle trucks like the most anonymous of his subjects. King of the chosen ones. Soon this tribe walked like ghosts. When they ended up in the camps they soon stopped walking. They were incapable of movement. Nothing mattered to them. They were without thought. They were without reactions. Without souls you might say. Strangely, their smell and sound I remember more clearly today than I did when I was there.

It has taken me many years to remember those days. The others have tried to forget them. An old comrade who has lived here as long as I has shown me some films he had taken in the East. They built large pits for them there. There was no time to build monuments. They had to go about their business quickly and brutally. In this film they were running — running towards a pit as if they were going for a swim. I was there — in the East for a time — these mounds of flesh could be seen in almost every place our men had held firm. Mound after mound. Symmetry. Symmetry in Poland. Or the Ukraine. The same smell. The same sounds. These were almost perfect pyramids of flesh. The smell was overwhelming. The only way to eliminate this smell was by setting fire and turning to ash these little mountains. The flames jumped very high. I had never seen anything like it. This was a skyscraper of skin in flame. During the fires it began to smell of chicken. Rotting chicken. A sweet but powerful smell. It lasted a short time. In that moment it seemed to linger over the continent. God be with us — what a smell. I always felt a strange excitement when I was on site of these events. Watching some ancient and sacred act.

I spent too much time with papers. Numbers and dates. Timetables and deadlines. I spent too much time talking. But to be on site and see what those numbers meant. That was glory. It gave me a sense of myself I had not felt before — certainly I have only rarely felt it since. I'm not ashamed. One had to be there. We nearly rid ourselves of our misfortune in such a short time. Who, ten years earlier could even start to imagine how effectively we would deal with the problem. That's for sure. We nearly wiped Europe clean. Observing those neat pyramids — who wouldn't feel pride in that order. There hadn't been order articulated in this way for centuries. If ever. This flame we set up all over Europe.

We always had help from the locals. They were only too eager to help us with our problem. They had already drawn up their own lists of the ones who had to go. They added fuel to the flame. Sometimes they even started before we got there. Taking them from barns and attics. They would take the hunted and put them to the flame. Now these vermin join forces with their old enemies and lay all the blame at my door. Well, I didn't shrug off my responsibility then and I will not now. What do they really know of our task. Nothing. Nothing. My task began too late. Who would have dreamed we would get so close. So close to finishing off our problem. So many of them had entered our world when I was a young man. All seats of power fell under their sway. Rats who laughed in the face of our beauty. Thinkers, book learners the lot of them. At school these effetes would spend all their time in the library. A group of lads would often wait for them to run home and help with papa's business. So when they come out of the library we would jump out and give the little rats a hiding.

Seeing my father go to them with money it had taken him a long time to earn and he would always come back with next to nothing. I can still see him crying at the dinner table. I wanted them all gone then. These longnoses carried grief with them like it was an adornment. So many in our nation were caught up with them in one way or another. I could see this so clearly. I became a man who wanted to change the world. What a world. Men who had worked hard all their lives pushing a wheelbarrow full of money to buy food for the family. There wasn't enough. Families had their life savings go up in smoke. In one day. In one week. Well, the cause of our misery went up in smoke. In one day. In one week. I paid them back in full.

I worked once for these longnoses after I left school. I couldn't get a decent wage from them and while you were working you'd see them in a group all huddled up babbling away in an unheard of tongue. I worked for them for nearly two years. Selling furniture. I was a travelling salesman. I was a good talker and I made these bastards a pot of money. I was as good as them with my tongue. I had people buying furniture they couldn't afford to put in their shabby little houses. When the hard times came — they threw me out of work. On to the streets. They looked after their own. They threw me out. I'd made these rascals a handsome living from my talk. Threw me out. In those days there was ways to get back at them. I joined a political grouping. The national socialists. They understood our problem — our misfortune. They were active in the streets. That was the place I knew. Those who rule the streets rule the people. That was clear.

I threw myself into political work with the same fervor that I had sold furniture. I was a young and healthy man and I had plenty to offer a political organization. I was a good man to have in the streets. We fought it out with the Communists and Social Democrats and anybody else who was game enough to do battle with us. In those early days a man who could use his fists could exercise political power. I learnt on the streets how a society functions. I had too much respect for government before this. I thought the old fools on high actually knew what they were doing. I lost that respect very quickly. It's true that the reds were pretty handy with their fists but their leaders would tell them one thing one day another thing on another. One day we were the enemy. The next day we were friends. Soon no one would face us in the streets. They all hid in their shops and houses. I also ran meetings with an iron hand. I was a staunch comrade and it was clear to the leadership that I was a man who could follow and administer their orders.

It was quite early in the day when I was asked to join the S.S. When you are asked to join an elite organization you don't have to be asked twice. When I was asked to join everything formed in my mind so quickly. It was clear that as a country we needed a backbone. Our country was falling apart. It needed men like us to put it back together. Who else could have done the work? We had the political will to clean it up. There can be no suggestion that we did otherwise. We entered the fray with a fever. We were prepared to get our hands dirty. Who else would have been equal to the task? In the early days I made it my business to understand our enemies — our misfortune. I learnt their mongrel language. I made a point of going over their history. I laid my hand on all the magazines and books they produced on their cause. I was methodical in this. So methodical that my superiors noticed and knew what they wanted to do with me. They got me to write small studies on the yids for all manner of bureaucrats and to write notes on the question in handbooks for our soldiers. I was an authority. The others guessed and huffed their way around the question. Peasant superstitions held sway. Any old story was good enough for them as long as it cast the Jew in bad light. That wasn't good enough for me. I needed to know more. We needed to know more. If we were to rid ourselves of the problem — we had to set about the question very thoroughly. It was one way in which we could really do them some damage.

I don't mind saying that after a short time it had become an obsession with me. I'm sure some of the old comrades just thought that I was hunting for promotion but these same comrades were hungry to go to Palestine when the Party ordered me to go there. Who paid for me? Not the Party. The Jews. They paid for me to go there. Some of the smart ones knew what was coming — they wanted to set up there. A spiritual home. In a desert. I could help them. That's what I said. They knew the time would come. If it wasn't us it would be somebody else. I wanted to give them a little push. That was all that was needed in the first instance. A little push towards the sea. It was a botched trip. Travelled all over the Middle East. Except Palestine. Though I met some of their number who had already set up their suitcases on this continent. Typical of their race. Small people with big ideas though I treated them like gentlemen. They were going to conquer Palestine. You can have it I thought.

I was called back and thanked for my work. My superiors could see that I was on to something. I could see a political solution to our problem. I could see that if we allowed them to emigrate to the desert or some other sandy exile — we could make a great deal of money from them. Make them pay. They'd have to leave all their goods and chattels. Hand them over to their rightful owners. It had to be run well and I'm sure now as I was then that I was the only person to do the job. I had everything at my disposal. More so than some other comrades who were happy to get rid of them in any old way. No, I saw that there were more efficient ways.

When I came back I was sent immediately to Vienna to set up a Central Office for Emigration. We'd get them to pay their way out of trouble. Rich and poor they would have to pay to get out. I employed some of their number and they were happy to seek out their own. Together we'd work out what they would have to pay to emigrate. It was the best way. Early in the game it was better to be seen dispensing justice. We didn't want to appear to be savages. Those who instantly wanted to put the Jews to the torch missed the point. Throw them at the world. Watch the world throw them back. There would be time. Europe was falling apart. Any fool could see where we were heading. Only those who wanted to hide their heads failed to see what direction we would take. We were going to do the dirty work for the whole of Europe — that rotting piece of meat left out in the garden for the dogs.

In the beginning I stole ideas from their leaders. Took their ideas about creating a spiritual homeland. Turned it upside down. It had to serve our interests. Who in this world would have known? Who would have cared? No one said anything. Least of all the chosen ones. No they all held up their hands up like students in a yeshiva and said yes. Today these scoundrels lay the blame at my door. I'm the one who caused all their trouble. Yet they also had their hands in it from the beginning. I was a functionary and I had become an expert. Even they must admit that I expedited matters fairly quickly — concerning their welfare. My commitment to the work was beyond question. There were those who were offended by the zeal with which I took up these duties. Where are they now? These fools who imagined the affairs of state would leave them with clean hands. One, Dr. Muller, a superior who wrote of this and that deportation. A cultured man. He would write reports as if he were writing a novel. Muller always seemed so taken with the task that I decided he should visit a camp. One that was still in construction. We drove there and all the way there he spoke of the holy task we were performing peppering the conversation with quotes of our learned predecessors. How proud he was that he had been chosen to do this work. When we arrived at the camp we were treated to a large banquet by a vulgar little Bavarian who had been placed in charge. He said our presence was fortunate since that very day they were expecting a transport and all the chambers were now in full flow. Would we like to see it — he said? Of course — my superior replied. Wetting his pants at the thought. We watched as the transport was separated.

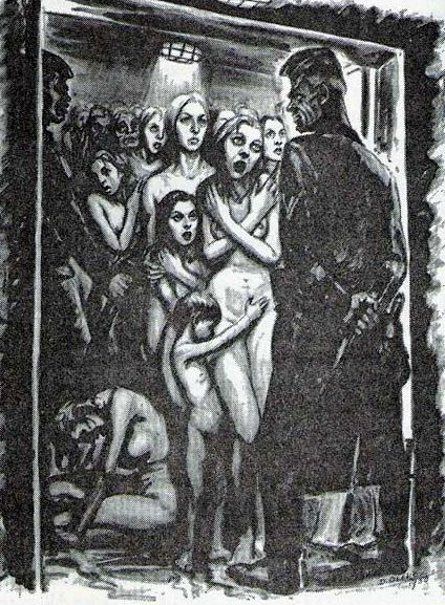

Soon the selections took place. Broken up into those who still had a bit of work left in them and those that could go immediately? A doctor colleague with a riding crop just stood there picking and choosing. Those from the transports seemed unclear about what was happening to them. Though you could see in some of their eyes that they had grasped what was going on. These said goodbye to their friends and loved ones. You would have expected these people to break down. They didn't. Once they were chosen they set about their task single-mindedly. The ones who went to the washhouse marched in formation. We followed them. We sat in a cubicle which was installed so you could have a clear view of what was happening in the washhouse. The washhouse was very full now. Almost to the brim. They shuffled against each other. Cattle — I thought. They looked like they were at some religious gathering. They seemed to stare everywhere except at each other. The gassing began. People looked up as if they were seeking some sort of guidance. Some realized what was happening and they began to scream. It wasn't the type of scream. It wasn't the type of scream one hears at a car crash. It sounded almost operatic. It was a scream that sounded for all the world like it was being sung. It was like watching some perverse form of opera with a cast yelling and running at each other. A restrained pandemonium. People started to pull at each other. They were actually tearing at each other.

Pulling and pushing like the other person was a door through which they could get out of this place. This was all happening very quickly — I must tell you. It was happening very fast. But for my superior and I it was like it was happening in slow motion. The screaming was so voluminous that is sounded for all the world like some mad opera being performed by inmates at an asylum.

Then something very strange happened. People started piling themselves into heaps in the middle of the floor. They were going a bluish kind of colour. They were piling themselves into a perfect pyramid ripping at each other as they did so. This was a sight I could never forget. I was so taken with this sight. So in wonderment at the nature of human frailty that I had not noticed my superior was sitting there with his hands between his legs. Vomiting. He had vomited all over his uniform. He stank of the most wretched smell imaginable. There were tears in his eyes. I imagine from the retching he had obviously done. I tried to clean him up. I tried to talk to him. He was past speech. He could not be consoled. How a man could be involved in this work for so long — I thought — and only now see what it meant. Pathetic. I couldn't muster any respect for him after that but he kept on with business as usual. These fools who would bore you day and night recounting our triumphs as if they were waging the war single handedly from the office. It made me laugh. At times I had no escape from their imbecility. Their endless chatter.

Now this fellow runs an agricultural machinery business which has business with the European Economic Community and with Israel. He is a man of influence now as he was then. I read that he was involved in politics at a very high level. Heads some committee for the government on industrial democracy. Some of us came out of the war unscathed. Dust your jacket and get back on your feet. One didn't even have to change their history if they were important enough for the Americans. They used me in the beginning. I had kept exemplary records. They forgot about me soon enough. Muller, the old fool walks away from the war without a scar. I imagine he was one of those who profiteered after the war at the people's expense. Another irony. Those who ran the black marketeering after the war — highly placed officials and our misfortune. What was left of them? I cannot today even contemplate the poverty I saw then highlighted by the opulence with which the Americans paraded through our streets. Our people were left with nothing. Not even their homes. What homes still existed were lived in by the occupying powers. They treated us like we were so much rubble to be tossed over. Some of us had something to sell. Scientists were picked up in the first weeks. Americans left no stone unturned. It took them a short time to find all the scientists they needed. Our whole intelligence network went over to them taking all their files. We had warned them against the red hordes and now they were finally listening.

So many times during the war — I thought they should come to our side and we could fight the Reds together. Get rid of them once and for all. Stalin was as cunning as he was slow. Fooled the lot of them and ended up with half of Europe as his prize. We made that mistake. We underestimated them. We had to pay the price. He too picked off our best and took them back or set them up in the Democratic Republic. They all covered their own arses. They were all a little careful about their histories. I wasn't interested in covering myself. I knew what I had done and was proud of it. I knew that they wouldn't want to understand. They would use all my information just the same. Let there be no mistake about that. They could use a man who kept exemplary files and they could use what he had in his mind. The end — I try to forget — not because we lost but because our people acted so shamelessly in front of the conqueror. None claimed responsibility. They all blamed someone else. I was a repository of their blame. Heimman did this. He ordered that. I was only following Heimmans orders. My superiors were not too superior because they offered the excuse that they were following my orders. My name seemed to be on everyone's lips.

For Part 2 click HERE

The Real Camelot

As we stare into the abyss of an unknown political future, let’s take a moment and appreciate what we have.

I was born during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower, arguably the last good Republican President. That year segregation suffered its very first push back. Lynching in the South was still common place. Hate for large groups of citizens like African-Americans, Native-Americans, Latinos and Jews, just to name a few, was so built into American life, that for most white people it was usually taken for granted.

By the time I was in elementary school we had a President, the first of Irish Nationality and the first non-Protestant, who made real strides in making things better... Just a few days ago we acknowledged the solemn anniversary of the assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

During an interview with Theodore White for an essay in Life magazine, Jackie Onassis shared that John F. Kennedy had been a fan of the Broadway musical Camelot, the music of which was written by Alan Jay Lerner, one of Kennedy's schoolmates at Harvard University. "Camelot" refers to a kingdom ruled by the mythical King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table. Jackie said "There will be great presidents again, but there will never be another Camelot." This echoed a line from the musical when the King Arthur character sings, "Don't let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief, shining moment, that was known as Camelot."

I propose that not only was Jackie wrong about the never again part, but that history will soon recognize we all just lived through America’s TRUE Camelot. The eight years under the leadership of President Barack Obama have been remarkable in many ways. His list of achievements may be longer than any, at least since Franklin D. Roosevelt. I have listed a few of the highlights here and there is a far deeper list in the link at the end of the article.

Partial list of Obama’s accomplishments in no particular order:

- Signed $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

- Biggest job growth in manufacturing since the '90s

- Auto industry breaking sales records

- Clean energy production doubled

- Unemployment cut in half

- Deficit cut by three-quarters

- Stock market tripled

- The Dodd-Frank Act

- Obamacare

- Killed Osama Bin Laden

- Normalized relations with Cuba

- The Paris Agreement

- Same sex marriage

- Repealed Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

- Reversed Bush Torture Policies

- Increased Support for Veterans

- Food Safety Modernization Act

- Expanded Wilderness and Watershed Protection

- Fair Sentencing Act

- Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act

- Expanded Stem Cell Research

Instead of delving deep into the itemization above, I want to focus on what he promised when he ran his first campaign; Hope and Change. Maybe what I really mean is what I and millions of people heard in that promise, as in a final fulfillment of the promise first made in the Declaration of Independence that "we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal".

And for eight years, in spite of everything that the Republicans and the new Tea Party could do to stop progress, what we got was a steady stream of movements to accomplish just that. We had a President who made clear his priorities were always based on doing the right thing. On trying to find compromise, in spite of obstructionism. On moving the United States and when possible the world, toward that elusive, but eternal goal of "liberty and justice for all".

Barack was intelligent, educated and eloquent. He was also very funny, a good singer and he could dance. He looked great whether in casual attire or white tie. His wife was also well educated and as classy as any first Lady and at least on par with Jackie. Their children grew up under the spotlight and never once disappointed as we watched them turn into beautiful young ladies. There was never even a hint of a real scandal in the Obama White House. Not of the official type or of the personal type. For eight years the only scandals were those the Republicans continuously tried to invent so as to try and impeach him, later to discredit him and finally to try and add some type of asterisk by his name in the history books, all to no avail. Like Jackie Robinson, he was the right black man to break the color barrier... and do it with a grace few others could touch.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not a sycophant or blind follower and yes there were decisions I did not agree with, but overall I look back on a period where the leader of the free world was admired by our allies, feared by our enemies and respected by all but the most die-hard racists and troglodytes.

So as I prepare to spend time with friends and family, on a day that our nation long ago reserved for appreciating what we have, I will give thanks for having had the privilege of living through what may well be the pinnacle of America’s history. Thank you President Barack Hussein Obama, we will not see your like again.

To repeat Jacki O’s quote in a context that is verifiably true; "There will be great presidents again, but there will never be another Camelot."

Full list of: President Obama's accomplishments